Nate Rouse dot com

Links

- CV

- Medical History

- Contact

January 10th 2022: The First 30 Seconds of Silent Hill 2

2001’s seminal hit Silent Hill 2 is a challenging, provocative and thoughtful work of narrative fiction. One which utilizes the established language of cinema and the, at the time, new and fluctuating language game design to upend established ideas about video game narratives and the place of the audience in examining them. It is a game which begins weaving its intricate narrative from the very opening moments and rarely lets up.

After receiving a letter from his wife, who died three years ago, James Sunderland travels to the town of Silent Hill, believing that she may somehow be alive there.

Upon starting the game, one is confronted with the protagonist and player character, James Sunderland, gazing at himself through a public restroom mirror in a claustrophobic close-up. Static and uncannily disaffected: James alienated personality is on full display before he has even said a word. He watches himself slide a hand over his unchanging face. Here is our first piece of formal intrigue. Real time rendering was a few years away from being able to handle complicated facial animations outside of cutscenes (Half Life 2’s groundbreaking in-engine facial animations wouldn’t exist until 2004) and so the stilted unreactivity of James’ animation would’ve been par-for-the-course in terms of real time capabilities. However, this sequence was not being rendered in real time. It was a pre-rendered, full motion video and one of the best in its class. The juxtaposition of the highly textured, highly rendered 3D animation and the fractured movements common to real-time rendering work together to create a thoroughly alienating sense of James. This, in the first moment of the game, represents the virtuosic understanding of the aesthetic language of video games that Silent Hill 2 would come to be known for. His body and mind are in two distinct places, operating holistically to present an atomistical subject.

In film, the 180 degree rule is a formal technique for preserving the continuity of a scene. It is visible in practically every shot reverse-shot conversation in film and television alike. However, the presence of this rule is never more obvious than when it’s broken. The example of Gollum/Smeagol from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers comes to mind. In this scene Gollum/Smeagol has a kind of psychotic break while debating with himself about whether or not to kill Sam and Frodo. Peter Jackson illustrates his fractured psyche by breaking the 180 degree rule, switching from left to right shoulder to represent which side of him is speaking. The same technique is used here: as James steps away from the mirror and our close-up cuts to a medium shot, the rule is broken: switching from right to left shoulder (and at the same time switching from pre-rendered to real time rendering). This has the dual effect of presenting James as a fractured subject, especially when in tandem with the characterization that’s already occurred, and complicating both the audience’s and James’ relationship with the mirror. A telling moment and key piece of foreshadowing given the games lynchian fixation with mirrors and duplicates: throughout the remainder of the game James will occasionally enter into a mirror version of the town Silent Hill, various characters appear to be identical to each other, and corpses which use the same model as James litter the town. This opening scene provides the tools to understand this mirroring as a psychological metaphor, and more specifically as a psychological metaphor for James: as it is his mirror which the camera first enters at the beginning of the game and his mirror which the audience never leaves.

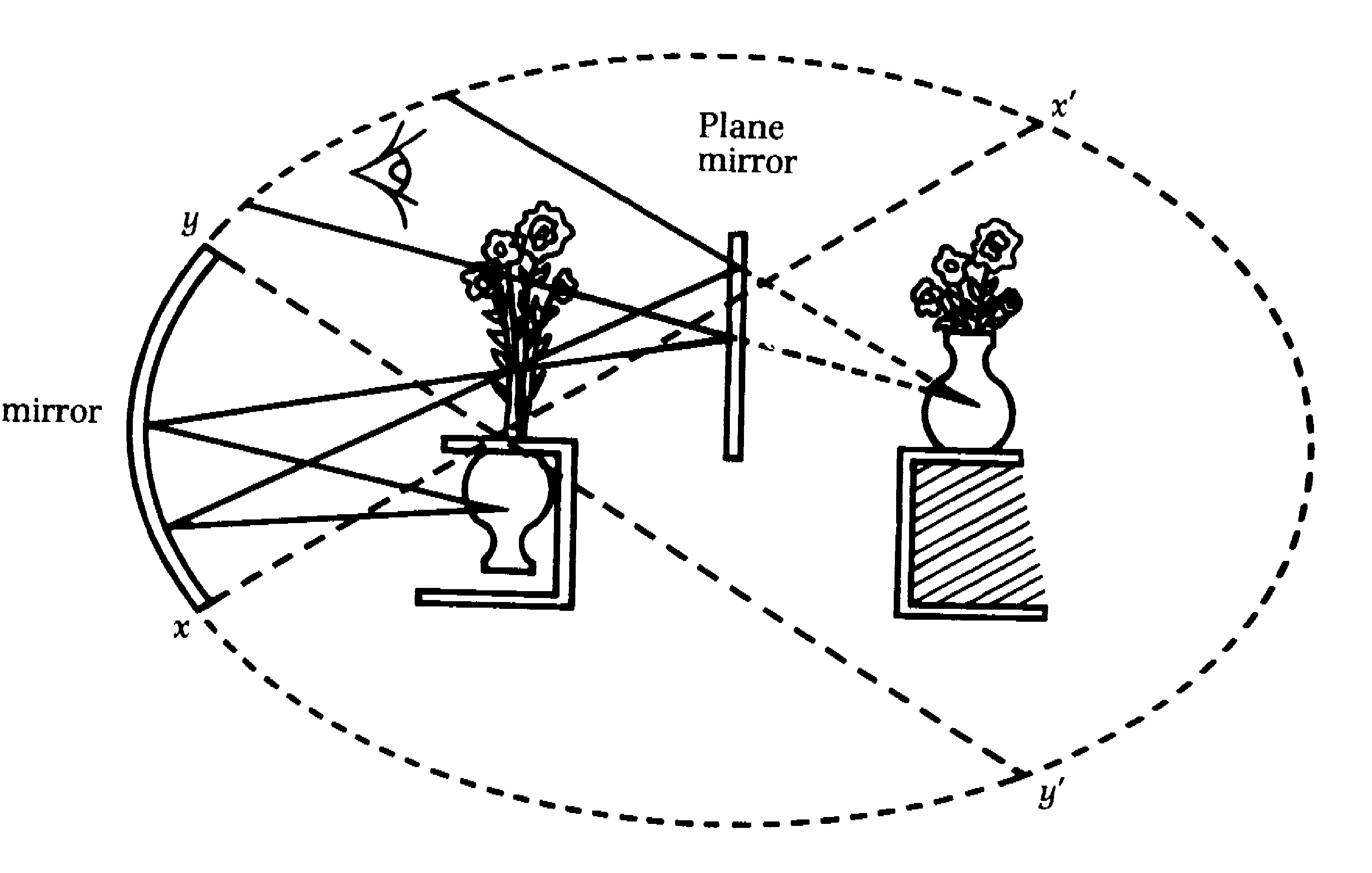

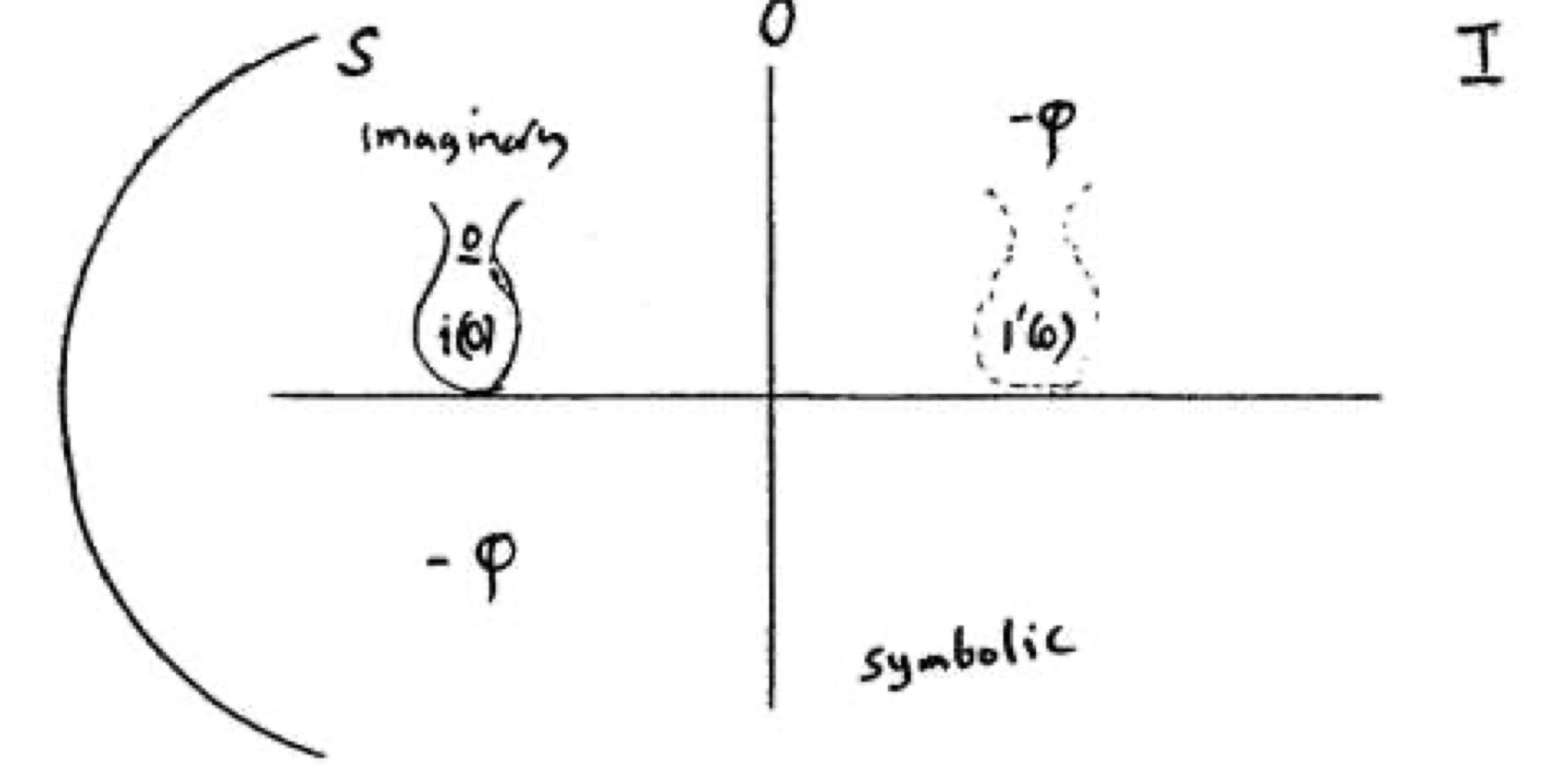

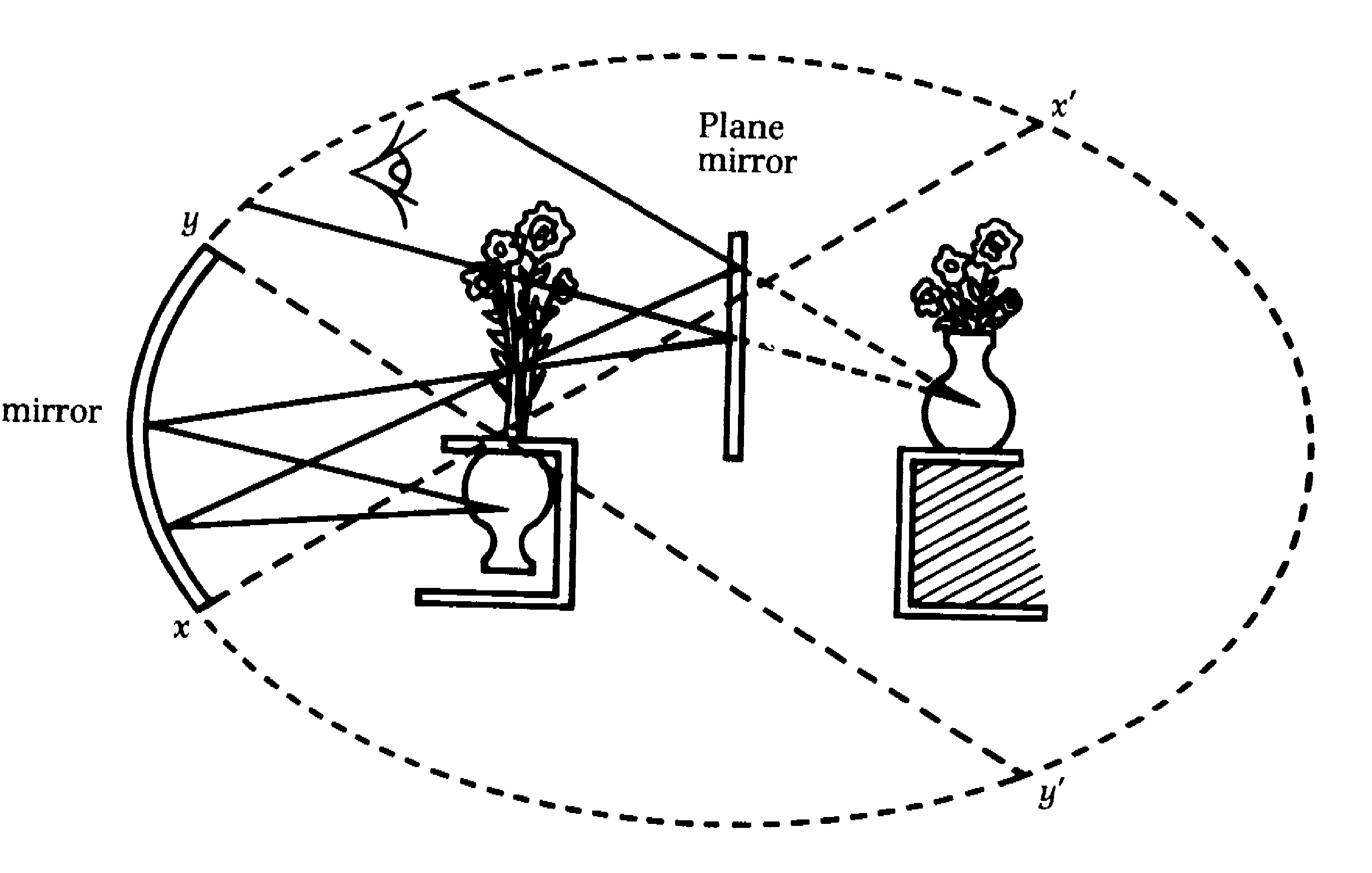

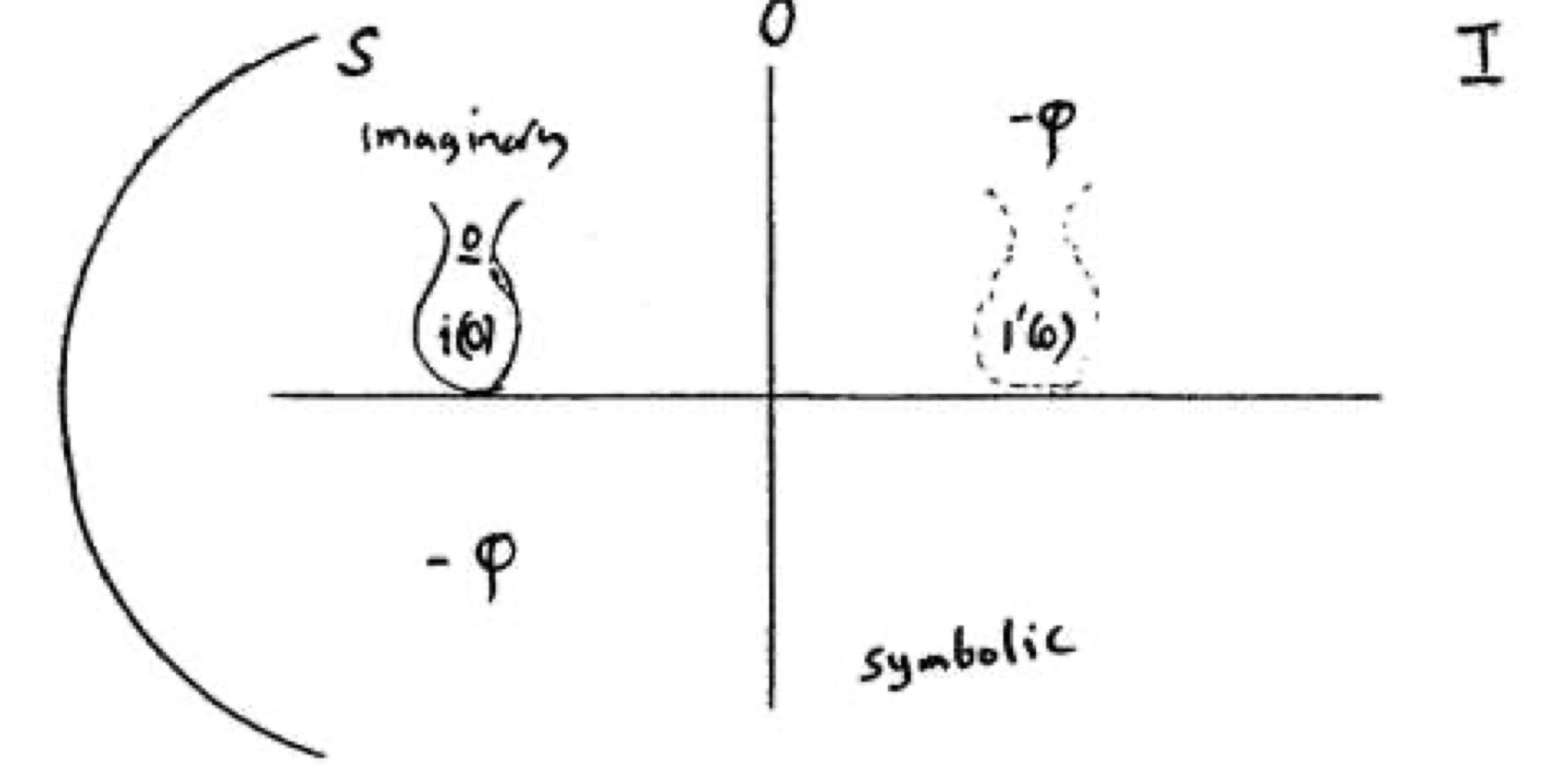

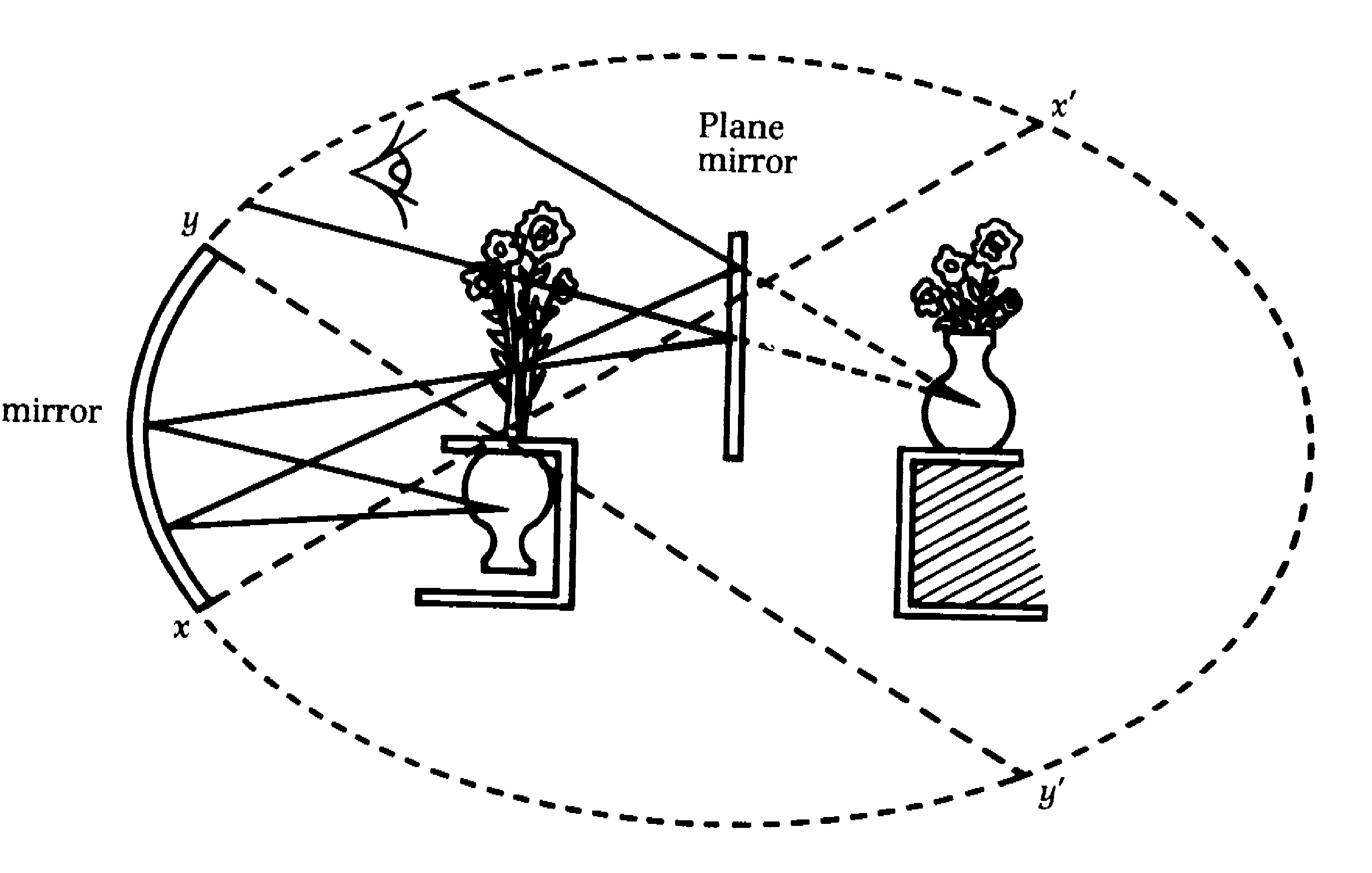

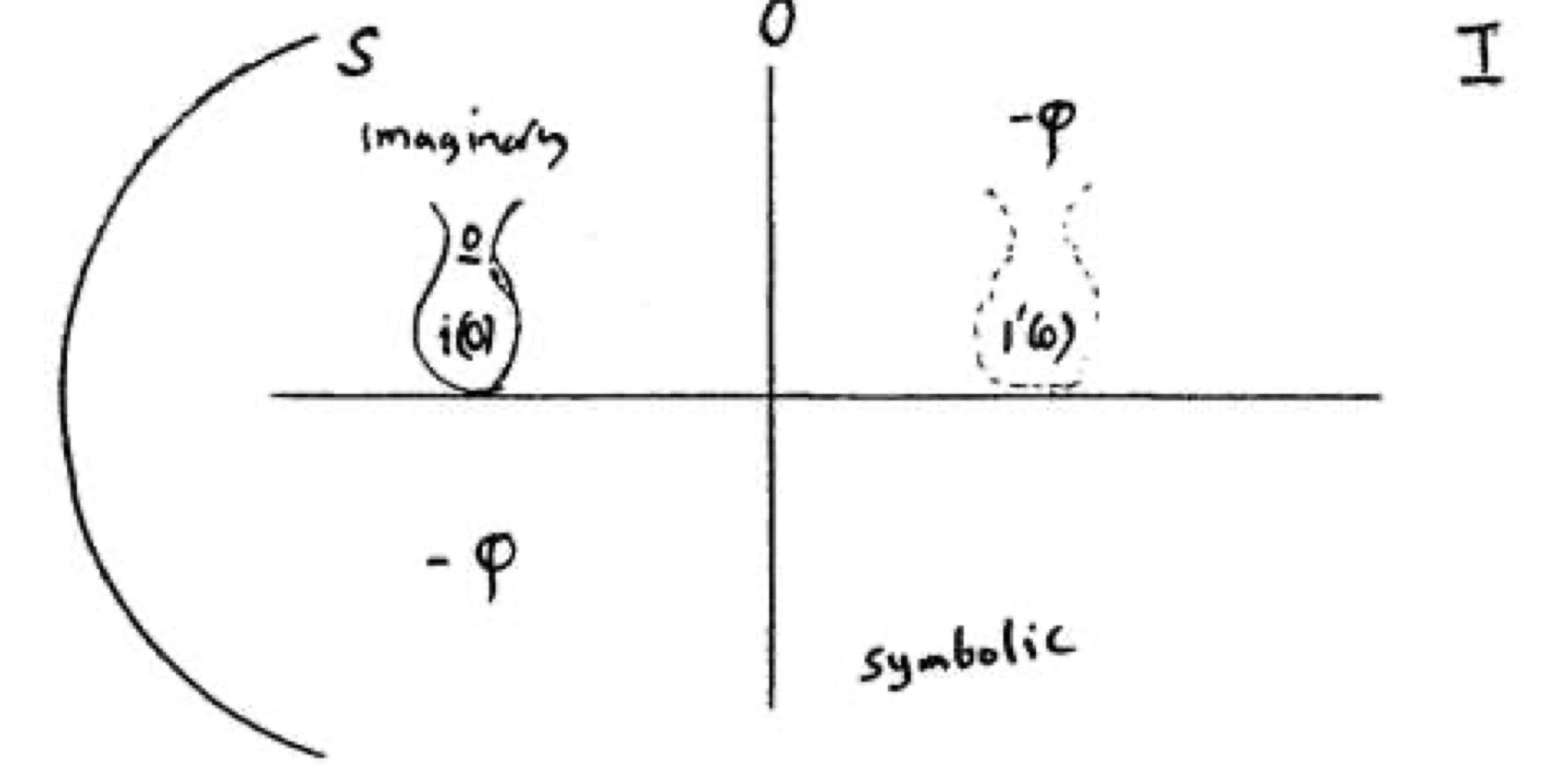

The Optical Schema (figure 1) is a metaphor used by the French developmental psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan as a way of describing a number of things throughout the course of his career. Here, we’ll be using it in reference to his 1962 seminar on anxiety wherein the drawing (figure 2) is used to illustrate the relationship between the imaginary, the real, and the symbolic as its discovered in the mirror stage. On the left hand side is an eye (S) which represents the subject. This subject, much like the subject of this writing, gazes into a mirror wherein it observes a construction: the completed vase, filled, as it ought to be, with flowers (or in figure 2 it is filled with Lacan’s symbol for lack). However, this construction is an imaginary one, as next to the subject is the real optical schematic, revealing the truth: the flowers are not in the vase, but separated. In other words the mirror makes apparent those things which the vase is missing. Because this lack is projected onto the subject, the subject is made aware of, what Lacan calls, "la objec petit a’’ or the object of desire. This object can be projected onto anything at all, however, it is impossible to ever receive.

|

figure 1

|

|

figure 2

|

So what does it mean that James has, as it were, entered into the world of the mirror? As Mike Drucker puts it in his book Silent Hill by Mike Drucker ’’James is so singularly focused that we immediately wonder if something is wrong with him. At the very least, he’s so disconnected from the utter strangeness of the town that he ironically fits right in.’’ (Drucker). What James is singularly obsessed with is, interestingly enough, finding his dead wife. A desire that is ostensibly unachievable. In this sense, the town of Silent Hill can be seen as a kind of spacial optical schema. It is a world wherein the unconscious desires of those who go there are made manifest. It is a world where the empty vessel of James can be filled with that which he lacks. This is why ’’[James] fits right in’’, because he is in touch with and, apparently, aware of his own lack he appears as an empty vessel. The audience is never made aware of any other character trait. As Drucker says just a few paragraphs earlier ’’We don’t know what James did for a job, what he likes and dislikes, or even how he feels about his life. Outside of his mission to find Mary, James seems to barely exist.’’ Outside of his (projected) desire, James is filled with nothing at all. Much like Lacan’s vase.